Monetary Policy in the Wake of Climate Disasters: Pakistan's Experience and Possible Solutions

In 2022, heavy monsoon rains and melting glaciers brought massive floods in Pakistan that showed how costly climate disasters can be. The floods affected around 33 million people, with more than 1,700 dead, causing damage to homes, animals, and jobs.

This blog explores the economic impacts of these floods, the specific challenges they pose to implementation of an effective monetary policy, and innovative approaches to incorporating climate risks into monetary frameworks and economic planning.

Economic Consequences:

The agricultural sector, a cornerstone for Pakistan's economy, bore the heaviest impacts of floods with key crops such as wheat, cotton, and rice destroyed at a massive scale. Such losses increased food shortages and drove up food prices, creating inflationary pressure in the economy. To illustrate the impact on inflation, some prices saw an increase of above 50%, such as the rice prices grew by 80% on a year-on-year (YOY) basis.

In response, the State Bank of Pakistan (SBP) announced that inflation would peak in early 2023 before gradually declining, as the effects of a tight monetary policy would take time to transmit completely State Bank of Pakistan, First Quarterly Report 2021-22 (2022). SBP expected the monetary policy to stabilize commodity prices. However, recovery from flood disasters was extremely costly and had put intense pressure on Pakistan's fiscal resources, making it difficult to provide prompt relief.

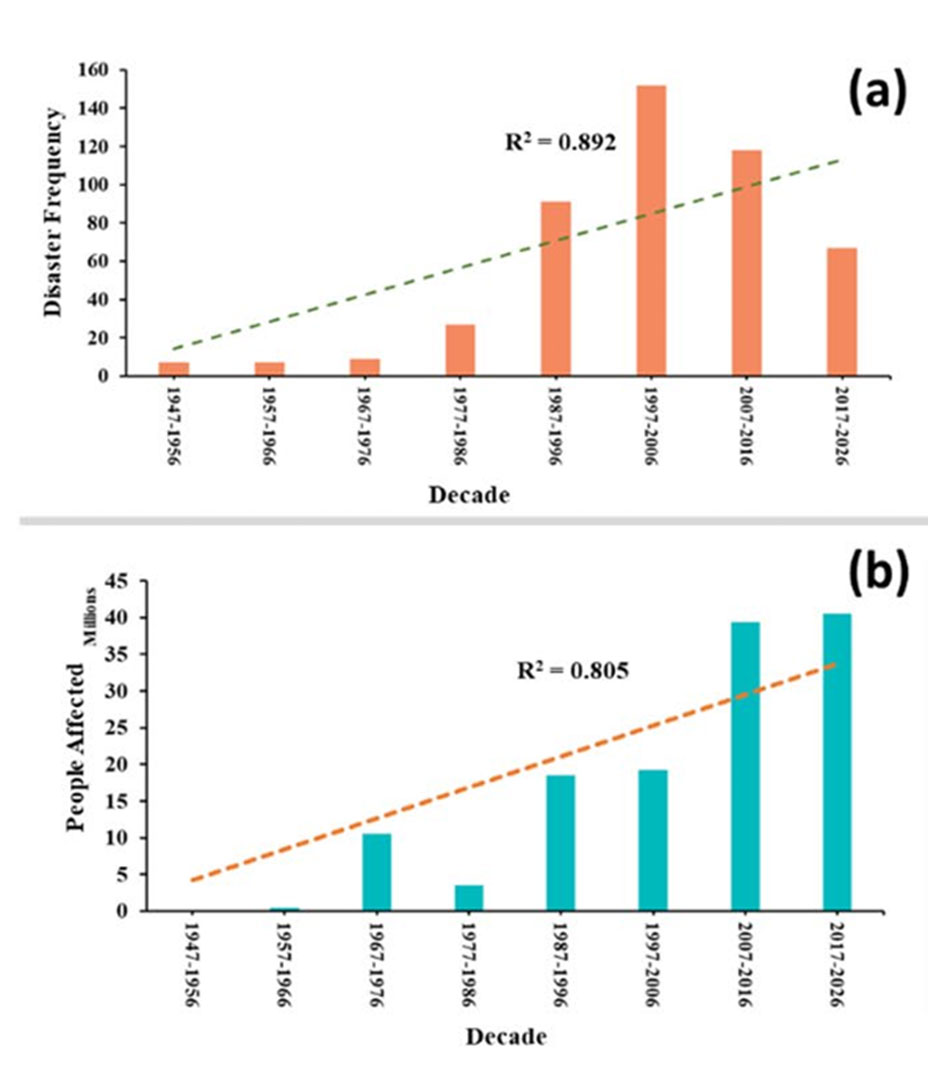

The increased frequency of climate disasters in Pakistan and their impact over the years is shown in Figure 1. Disaster trends, including the 2022 floods, raise climate risks that worsen Pakistan's economic woes, continuously depreciating rupee since 2019 after the conversion to a free-floating exchange rate. Inflation rose to 30.77% in 2023 from 19.87% in 2022, signifying the urgency of disaster recovery to maintain economic stability.

| Figure 1: Graphs show inter decadal variations in a) disaster frequency (number) and (b) People affected in Pakistan since its creation in 1947 (millions). Source: Sajjad et al., (2023) |

|

Challenges for Monetary Policy:

Climate disasters make Pakistan's Monetary policy less effective by injecting unpredictable, local shocks that cannot be mitigated through broad, economy-wide tools like adjustments in interest rates. The SBP raised interest rates to 17% to control inflation which was driven by crop failures. However, this measure inadvertently limited access to credit, hindering recovery efforts for businesses and the agricultural sector that were in urgent need of financial support.

This challenge is further driven by Pakistan's dependency on imports for its raw materials and the volatility of its currency. Supply-side shocks, as a result of climate disasters hike prices for necessities, keeping inflation high especially when the rest of the economy is already suffering. This situation represents a policy dilemma: higher interest rates risk undermining the recovery effort or a loose monetary policy that would fuel price inflation.

Rethinking Monetary Policy for Climate Risks:

Central banks around the world are reassessing their policies to better address the economic impacts of climate-related disasters affecting the economy. For instance, the European Central Bank started integrating climate-related data into its econometric models to enhance policy responses.

Similarly, Pakistan could incorporate climate-adjusted inflation targeting to develop policies that support both recovery and long-term economic resilience. SBP could further strengthen green finance by offering loans for renewable energy projects or climate-resilient infrastructure at more competitive rates. Such measures would not only strengthen the prospects of recovery but also ensure that the economy is better prepared to face future disasters. Additionally, coordination between fiscal and monetary policy is crucial. While the central bank stabilizes inflation, the government could offer relief packages such as subsidies or cash transfers, to support households severely affected by climate disasters. As fiscal support could further exacerbate inflation, the institutions must find a balanced way to support the needy with minimal inflation hike.

SBP can create climate-related financial instruments, such as catastrophe bonds, to enable fundraising in times of calamities and support strength-building initiatives. Special loans for climate-smart agriculture could be provided to rural communities, such as flood-resistant seeds and irrigation systems that reduce agro-biodiversity risks.

Early warning signs, for example forecasts of temperature and rain from Meteorological department, related to possible climate catastrophe could be integrated in the monetary policy decision making. This would allow SBP to anticipate economic disruptions and provide early solutions like low-interest recovery loans.

Sustainability should be at the core of SBP's decision making process, implementing climate stress tests for the financial institutions can help them prepare for any shocks in the financial system. Pakistan could also collaborate with neighboring countries to work toward a climate resilience fund and manage cross border flood management system. Additionally, public and private partnerships could play a critical role in financing infrastructure that does not easily crumble in floods, such as watertight housing and better water management systems.

All these initiatives would add extra support to Pakistan's monetary and economic systems for resistance against the next climate catastrophe, God forbid if it happens so.

References:

Sajjad, M., Ali, Z., & Waleed, M. (2023). Has Pakistan learned from disasters over the decades? Dynamic resilience insights based on catastrophe progression and geo-information models.

EGF Blogs

© Institute of Business Administration (IBA) Karachi. All Rights Reserved.